Features

Chronicle

Opinion

A chance encounter

How three Americans created the folding carton industry.

March 8, 2021 By Nick Howard

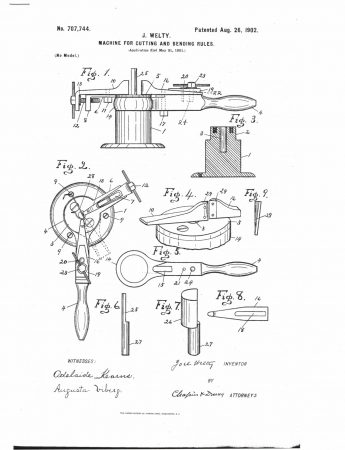

An operator forcing a Welty steel (hardened) rule (ca. 1902 and restored at Howard Iron Works Museum), to bend around the central round anvil.

Photo: Howard Iron Works Museum.

An operator forcing a Welty steel (hardened) rule (ca. 1902 and restored at Howard Iron Works Museum), to bend around the central round anvil.

Photo: Howard Iron Works Museum.

Despite what is currently on display now in the United States, both politically and in relation to COVID-19, it doesn’t impact how I see Americans overall. A great deal of my business life has involved working with our neighbours to the south, and I always found Americans more progressive than the rest of the world. It seemed that selling in the U.S. was much more accessible due to Americans having a more open and broad appreciation of whatever you were selling. It appeared they cared less about the little things and instead focused more on what the machine was able to do, and how it was able to make money for them. Americans tend to look forward, not backward. Perhaps this explains why so many genuinely great innovations come out of America.

Three innovators used this willingness to invent to take a unique idea and develop it. In 1853, 14-year-old Robert Gair arrived in New York City from Edinburgh, Scotland. An enterprising young man, in 1864, Gair soon set himself up as a paper jobber (buying and selling paper and cardboard goods) at a remote location in Brooklyn. With the arrival of newly-invented corrugated materials before 1870, Gair invented several machines to manufacture these fluted corrugated sheets. The idea of a paper box was still in its infancy, as most goods were either wrapped in paper with string or placed in veneer-wood boxes.

Three innovators used this willingness to invent to take a unique idea and develop it. In 1853, 14-year-old Robert Gair arrived in New York City from Edinburgh, Scotland. An enterprising young man, in 1864, Gair soon set himself up as a paper jobber (buying and selling paper and cardboard goods) at a remote location in Brooklyn. With the arrival of newly-invented corrugated materials before 1870, Gair invented several machines to manufacture these fluted corrugated sheets. The idea of a paper box was still in its infancy, as most goods were either wrapped in paper with string or placed in veneer-wood boxes.

In 1879, Gair went further and was credited with the machine invention that would produce “folding boxes.” In so doing, he is also credited with manufacturing the first pliable steel rule. The use of a metal rule was first attempted earlier when Gair had been manufacturing flat-bottom paper bags. One day a simple metal ruler used to crease the bags shifted, and instead cut a bag. That mistake lead to the discovery that in using a steel rule, both scoring and die-cutting were possible simultaneously, which prompted Gair to go on to manufacture prefabricated boxes. Later in 1887, the British printing giant E.S. & A. Robinson (soon to be known as the Dickinson Robinson Group) caught wind of Gair’s breakthrough and brought the technology back to England.

An old process called “dinking” actually predated Gair’s invention but not in the paper industry. Shoe manufacturers developed a sharpened die to cut out various shoe and boot parts appearing in the mid-19th century. Although occasionally used to punch metal, dinking techniques were closely held and seemed bespoke to shoes, and possibly other leather goods.

Along the way, Gair would amass a sizable fortune in New York City real estate, primarily in an area called “Down Under the Manhattan and Brooklyn Bridge Overpasses,” which the locals refer to as DUMBO.

Robert Gair set about patenting his invention in 1879. He referred to it as “the improved apparatus for cutting and creasing paper in the manufacture of paper boxes” when he swore an oath for a U.S. patent application. Unfortunately, Gair never completed the paperwork, and a U.S. patent was never granted to him. During the remaining years of the 19th century, the steel rule concept spread around the world as various industries appreciated its usefulness and labor-saving profitability.

Meanwhile, fast forward to Fort Wayne, Indiana, and an inventor by the name of Joel Welty. With no previous experience in the printing industry, Welty somehow caught wind of the need to bend and cut steel rule into intricate shapes for use in paper labels and gaskets. The device he would invent, in 1902, would form the next critical phase of steel rule die development, now including the growing paper-box industry. Branded the “Multiform,” this little gadget borrowed from similar technologies used in the sheet metal industry. The Iron-Worker, a multifaceted tool, still in everyday use, showcases some basic concepts Welty applied to invent his little bender. When I say little, I mean little, as it weighs less than 10 pounds with two levers working in an arc around a center mandrel. Just bolt it to a bench, and you were ready to use it. Welty sold quite a few; however, one lucky sale Welty made was to the Fort Wayne Paper Box Company.

The final phase would not appear until shortly after Welty died in 1910. On a spring day, John Richards, who hailed from Albion, Michigan, was returning to the train station after visiting his brother. The path took him past the Fort Wayne Paper Box building, and through the window, Richards noticed a young man using an unusual tool to bend steel rule. He enquired and found out that the device was made across the street. Off Richards went to meet Welty’s widow and purchased the patents, patterns and business of the J. Welty Co in a very short time.

As written later in Richards’ book, The Art of Die Making, he says, “[Welty] had sold [Multiforms] all over the world, but in a remarkable coincidence, I first saw it where it was designed and built.” No stranger to the printing industry, Richards had worked as a mechanic for the Miehle Printing Press Co. then the Campbell Printing Press Co. In 1906, Richards would start his print shop, which included making dies and even designing a bender.

Richards’ fortune would result in a dynamic business that would become the centre of a booming die-making industry – the J.A. Richards Company. Months later, the firm improved the original Multiform bender with a patent issued in 1911 and made substantial changes by 1913. With his growing family, which would eventually include ten children, Richards needed a bright mind and the urgency to support his brood. In 1916, the company relocated to Kalamazoo, Michigan. Rapid new developments in tools to manufacture complex shapes and now using Lignostone base plywood uncovered a further unique opportunity for Richards as these boards needed kerfs cut. Complex machines incorporating a jig-saw, drill and saw made it easier for a skilled die maker to create the inlay necessary to fit the rule.

Indeed, most of the printing and paper box industry is familiar with the J.A. Richards Co, but steel rule travels far beyond print. Metal punching proliferated with everything from fan blades, automotive body panels, and even aircraft components “punched” with equipment made in Kalamazoo. Then there are the gasket and fabric/leather industries, which quickly noticed the massive production savings using a hardened flexible rule that could be bent to any shape.

The J.A. Richards Co would remain in business until 2003. They prospered in both good and bad economic times, continually inventing and improving all sorts of die-making machinery. They also supplied special tooling, blanking-dies and die-board. However, the paper box industry was rapidly changing. The arrival of the laser, to cut a die board, started to eat into sales of mechanically jigged die-boards, and with it went the die-saw business.

Furthermore, computerized tools to bend the rule had left Richards without an answer in this segment as well, although thousands of Richards’ tools are still in use for smaller jobs or emergency rule repairs.

Today the remnants of the J.A. Richards Co are owned by the Porth Products Co in Paw Paw, Michigan. It was during an afternoon conversation with Mr. Karl Porth that I learned of the demise of J.A. Richards Co. I had called him to see about a replacement spring for a Richards cutter we were restoring for the Museum. Although familiar with the company, having bought and sold quite a few of their tools in the past, I had no idea of Richards’ historical background and mostly how vital Mr. Richards was in developing today’s flourishing paper-box industry. During that call, Porth mentioned he had an original Welty “Multiform” from pre-1910 and was gracious enough to donate it to our Museum.

We are indebted to Mr. Porth and also to the American spirit, which may not seem beaming as bright in 2020. I’m confident our “can-do” neighbour will be back again soon to continue bringing the world revolutionary inventions!

Nick Howard, a partner in Howard Graphic Equipment and Howard Iron Works, is a printing historian, consultant and Certified Appraiser of capital equipment. nick@howardgraphicequipment.com.

This article was originally published in the November 2020 issue of PrintAction.

Print this page