Features

Chronicle

Opinion

Invest in the present instead of worrying too much about tomorrow

June 27, 2018 By Nick Howard

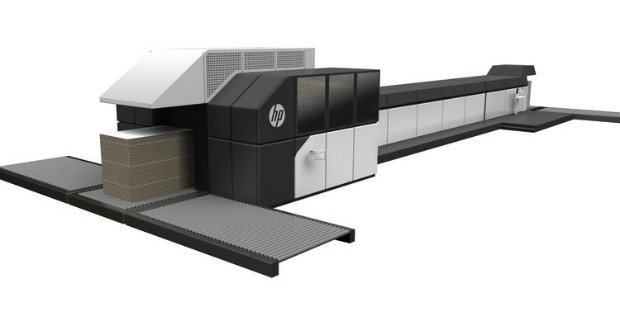

HP’s new C500 inkjet press is an example of new digital technology that could make a significant impact on the offset corrugated market.

HP’s new C500 inkjet press is an example of new digital technology that could make a significant impact on the offset corrugated market. The drupa 2000 trade fair was electric. World economies were coming through five years of growth and the dotcom surge was just forming a bubble. At drupa 2000, Komori showcased a press called Lithrone S40 Project D. Earlier, Heidelberg introduced a similar hybrid offset-digital press in the 29-inch SM74-DI.

By the end of 2001, a six-colour Project D was sold in Canada, but the company struggled with it. In part because its general operating procedures were so different, newly tethering two technologies in Creo’s SquareSpot direct imaging heads on an offset press. Heidelberg’s SM74-DI ran into the same problems and eventually most of the expensive Creo heads were removed. The SM74 turned back to be a regular offset press.

In 2000, everyone in the printing industry was abuzz over CTP imaging, but installing this type of imaging on a 6-colour press meant you had, in effect, six CTP devices. What looked like a logical next step in press efficiency turned out to be a bust. Add in the dotcom recession of 2000/2001 and it all conspired against what seemed like a great idea.

I’m always fascinated by how we make decisions. Reaching into the past offers us a sense of how the future turned out and the ability understand our mistakes.

In 1926, Vogtlaendische Maschinenfabrik A.G. in Plauen, Germany, produced what it said was the world’s first 4-colour offset press. Running at an astounding 2,200 sheets per hour, this seemed revolutionary in the moment. Soon the market was full of press builder’s offering similar technologies, but we already had 2-colour presses and a 4-colour was simply evolutionary.

In 1778, Georg Christoph Lichtenberg, a German scientist, came upon a technology that would eventually be known as electrostatic printing. Coating paper with zinc oxide and applying an electrostatic charge could create an image. By 1961, A.B. Dick Co. of Chicago had built an addressing machine for Time Inc. that could lay down 20,000 characters per second on narrow rolls of specially coated paper. That’s only 183 years later! Lichtenberg was also considered the father of what would become ISO 216, standardized paper sizes, which most of the world outside of Canada and America use today.

In 1964, America’s Harris Intertype and Mead went further and designed a larger roll-fed press that could print military maps at the rate of 2,000 5-colour images per hour. The printing industry was hungry to implement new technology and electrostatic printing looked like a Golden Goose. It was simply too early.

Chester Carlson’s experimentation with Xerography was still in its infancy and would finally prevail with symbiotic applications. Harris moved on from electrostatic because offset was its bread and butter. And Harris had just recently received its largest deal ever in a US$3.4 million press order from Western Publishing in Wisconsin. That’s US$28.5 million in today’s money and a heck of a lot of Golden Books. Keep in mind those presses had no consoles, electronics, plate-loading or other labour-saving devices. They probably were only supplied with ink agitators as an option.

The National Lithographer’s January 1964 article called Looking ahead in the Graphic Arts industry, estimated what the print world would like in the future. Its ideas stemmed from a new sector, labeled as electronics. Spurred on by new mass production of the transistor, the magazine explained how great minds were daydreaming about how these new tools would produce more print at less cost and higher quality.

Talk of an exposed plate from film without using a camera was but a dream. Neither the concept of reducing film flats to 2-inch microfilm rolls, nor then imaging (projecting) directly to a special plate on the press, went anywhere. I remember hearing a lot about the so-called one-shot skid printing concept: Take a flat (film), place it on top of a skid of paper and fire x-rays through the film to transfer the images through the whole skid. There was the idea to eliminate perfect binding by placing glue along the gutters of a signature during folding. Once folded into a signature the section is already bound. What about the whole book?

Some ideas did materialize. Automated proof-reading for one. Optical scanning of MICR codes another. Single-pass belt printing did make in-roads.

An early Canadian printer, Stroud, Bridgeman Press of Toronto, helped develop this idea whereby plates are mounted on an endless belt and could conceivably print an entire book in one revolution. The Cameron Belt Press came out of this and for a short time advanced.

Even though technology is constantly changing, one thing never alters: Our inability to see the future. We look at tomorrow’s challenges and try to improve on them with today’s prejudicial technology.

Truly amazing leaps in digital platforms are upon us right now. HP’s new PageWide C500 corrugated inkjet press, which can produce a massive 246 linear ft/min (75 linear m/min), will drive more business away from offset. Xerox’ six-colour Iridesse, including CMYK and two extras like metallic gold and silver, will reach further into the short-run market with a reasonable 120 pages per minute output. Let’s not forget the Landa system, which similar to HP’s Virtual Belt Technology (VBT), is coming. Every inkjet or toner manufacturer is actively launching faster and better platforms right now.

With the rapid change from offset to digital, it is best to not make hard decisions about tomorrow, but instead take advantage of what’s on offer today.

Nick Howard, a partner in Howard Graphic Equipment and Howard Iron Works, is a printing historian, consultant and Certified Appraiser of capital equipment.

Print this page