Headlines

News

The Spice of Printing Life

March 14, 2018 By Alec Couckuyt

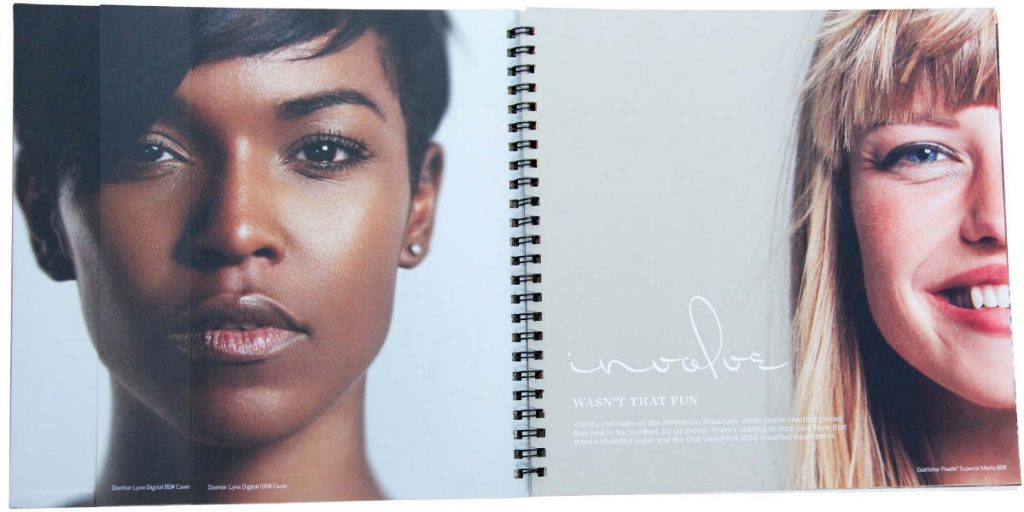

Variety, The Spice of Life Media catalogue, was produced in a 10,000-piece run by Canon Canada to highlight the inkjet effectiveness of its Océ VarioPrint i300 system.

Variety, The Spice of Life Media catalogue, was produced in a 10,000-piece run by Canon Canada to highlight the inkjet effectiveness of its Océ VarioPrint i300 system. For many commercial printing leaders, inkjet has reached a tipping point as the process becomes a relevant, quality production tool, initiating a third wave of technological change.

Variety, The Spice of Life Media catalogue, is a Canon-produced self-promotion project using 15 different papers to highlight the media versatility of the Océ VarioPrint i300. First introduced in Canada in 2016, this production-strength sheetfed press is equipped with iQuarius technology to enable inkjet printing at high speeds. It is designed to bridge the gap between the application flexibility of toner presses, the efficiency of offset sheetfed presses, and the economy and productivity of web-fed systems. It enables print providers to handle new and diverse applications with an eye toward productivity and profitability – benefits all inkjet press makers are leveraging.

Canon’s Variety project also highlights the use of Océ VarioPrint i-Series’ optional ColorGrip technology, which enables printing on a wider range of media, expanding the application range. ColorGrip enhances the image quality on papers not designed for inkjet. It expands the media range to include some coated offset stocks.

Production inkjet jobs can now include a variety of coated, uncoated and treated stocks and the printing system automatically adjusts the print parameters for each media type on a sheet-by-sheet basis.

ColorGrip and iQuarius, and of course the VarioPrint i-Series, are unique to Canon, but the movement toward commercial-printing relevance by new generation inkjet technologies from other leading vendors is becoming a reality in the offset-dominated world of printing.

The Variety project highlights that the days when inkjet presses could not effectively print on coated offset stocks are gone. Gone are the days when the quality of inkjet was considered almost there. And gone are the days when commercial printers once felt like they had to ask that million-dollar question, offset or inkjet?

Waves of change

If the question is no longer offset or inkjet, then what should printers ask themselves and their suppliers when considering capital investment for the present and future health of their businesses? In order to figure this out, I began tapping into my years of experience in this ever-evolving industry. Over the past 30 years, I’ve had the privilege to work for companies such as Agfa in Belgium, Germany and Canada; Transcontinental Printing at its large-scale plants in both Canada and the United States; Symcor – one of North America’s largest transactional printers in Canada; and, for the last 10 years, with Canon Canada. Throughout my career, I have been able to witness firsthand the many waves of technological change in our industry.

During my career, the first significant wave of change started with the introduction of the Macintosh computer in the mid-1980s, the subsequent digitization of prepress, and ultimately the launch of Computer-to-plate technologies – the latter largely pinned on Canadian-led development. This digitization of print basically eliminated many vertical processes like typesetting, imposition, colour separation and plate-making.

The wave of digitization in print created a business shift, allowing – if not forcing – printers to create a more streamlined process to move directly from file preparation to plate-making. The industry underwent massive consolidation because of digitization. I remember Agfa buying Compugraphic and soon after Hoechst – and subsequently how dramatically the graphic arts dealer network changed across the country.

The second wave of change started in the mid-1990s with the introduction of the first rudimentary standalone digital presses and digital inkjet print heads. Print jobs exceeding million-plus run lengths started to disappear and we entered into versioning and personalization. I remember installing the first one-inch Scitex inkjet heads on our half-web offset presses and the acquisition of our first Xeikon digital colour press at Yorkville Printing, owned by Transcontinental.

During this wave, we also saw the evolution of toner-based platforms (cut-sheet and continuous-feed marvels) in an adjacent industry. The transactional printing industry was dealing with large amounts of variable data coming off mainframes, printing transaction records on preprinted offset shells. At that time, transaction printers only printed in black-and white, no colour, and obviously all variable.

As the millennium year 2000 approached, transaction printers and commercial printers were operating in divergent spaces, serving different verticals.

Then came inkjet

We installed our first high-volume inkjet presses in 2008 in Toronto and Montreal at a leading transactional printer. These full-colour inkjet web presses ran 22-inch wide rolls of paper (52 inches in diameter) at speeds of nearly 500 feet peer minute. Massive amounts of transaction data and CMYK colour data were processed on the fly, now driven by powerful servers. More importantly, the introduction of printing full colour in a “white paper factory” model eliminated the need for pre-printed offset shells. This dramatically impacted overall efficiencies, including warehousing and logistics.

Inkjet printing fundamentally reshaped the transactional printing segment of the industry. Early adopters of this technology gained a major competitive advantage, captured considerable market share, and – again – market consolidation ensued. Inkjet had evolved but was not ready for commercial printing – not yet. But the once distinctive lines between transaction and commercial printers began to blur.

For many in the commercial printing world, drupa 2016, also dubbed Inkjet 2.0, was the tipping point for when inkjet became a relevant, quality production tool, initiating the third wave of change. The demand for short runs, full colour, quick turnarounds, and variable print work increased exponentially as the need for long print runs decreased substantially. Since the turn of the millennium, maturing toner-based, cut-sheet production platforms fulfilled these initial print consumer demands for short-run, full-colour print. Their inherent limited production speed and higher cost structures, however, limited the type of applications one could profitably take on.

The current generation of inkjet presses have now eliminated these production limitations and are breaking down cost structure barriers. Additionally, the range of capabilities and the quality output of inkjet presses make them suitable for at least 80 percent of all commercial printing work. But these are not the primary advantages of inkjet, they are a given. The single most-important attribute of inkjet is the capability of producing relevant printed products.

Inkjet is not just a technological evolution or change, above all it is the cornerstone in helping printing businesses stay relevant in a changing world of omni-channel communications – a world flooded by print, e-mail, apps, text, any number of smartphone capabilities, Web, streaming, virtual reality, etcetera. Inkjet gives commercial printers the tools to mass produce customized and personalized integrated print pieces almost instantaneously, and to be an integral part of the omni-channel communications sphere.

The ultimate question commercial printers should ask, therefore, is how do inkjet and offset fit into my business model and enhance the relevance of my offerings within the world of omni-channel communications. These are indeed exciting times for an exciting industry.

Print this page