Headlines

News

The Rise of Komori

October 30, 2017 By Nick Howard

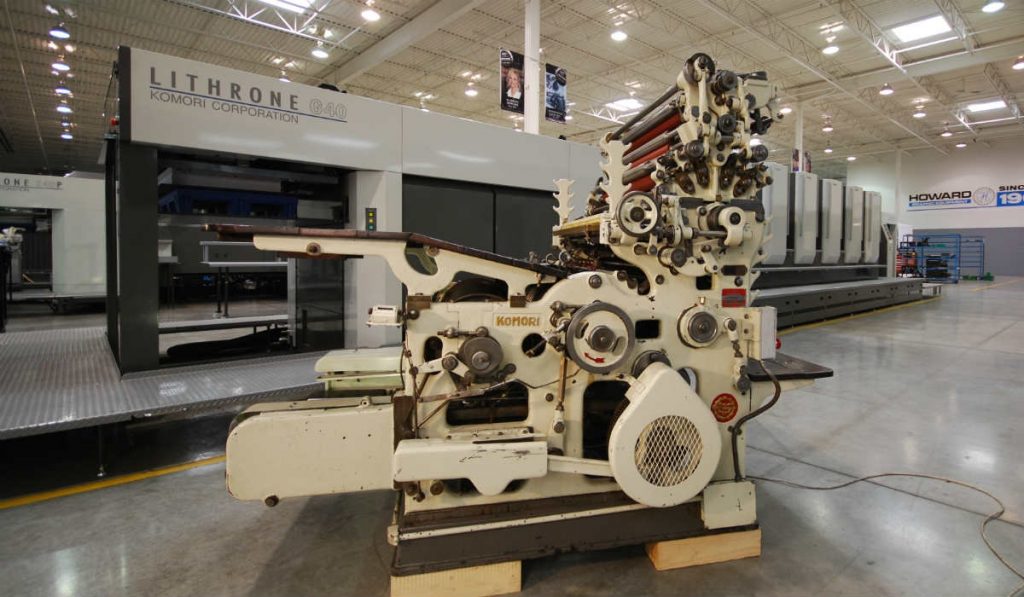

Komori’s hand-fed offset press, thought to be built in 1928, is a near clone of either the British Furnival or American R. HOE. This press, pictured in front of Komori’s impactful Lithrone platform, at Howard Iron Works was wrestled away from an English dealer.

Komori’s hand-fed offset press, thought to be built in 1928, is a near clone of either the British Furnival or American R. HOE. This press, pictured in front of Komori’s impactful Lithrone platform, at Howard Iron Works was wrestled away from an English dealer. Deep inside our Howard Iron Works Museum sits an odd looking offset press. Cast in the frame the words Komori along with the once familiar Bat logo. I managed to finagle this press from the hands of an English dealer. It took years to finally pony up enough cash to get him to sell it to me. For he was a lifelong Komori man and took great pride in having this press displayed in his factory. I was told it was built in 1928, but as hard as I tried, I was never able to verify this.

We had to make a couple gears for it. So after measuring we were all surprised to learn this little machine was built to imperial measurements and not metric. Why such interest? Container Corp.’s director of research said it best: “If you don’t remember the past. And are not conscious of the present, you have no future.” There are literally thousands of lessons to be learned and amazing stories to be told about our industry’s pioneers. Komori is but one excellent example.

Early Tokyo years

You don’t learn much about the early days for this Tokyo-based company and, as with all Japanese engineering firms, Komori is extremely careful with its reputation. It all started on October 20, 1923, when Komori Machinery Works was formed as a private business. The print world was just awakening to the new phenomenon called offset lithography and Komori seemed to take the position – quite rare in Japanese manufacturing – to enter an immature market instead of building what everyone else was, namely letterpress machines.

As near as I can research, the press we have, which is hand-fed, is a near clone of either the British Furnival or American R. HOE. After the U.S. discovery in 1904, lithographic offset sprang to life in Japan. Prior to 1920, the Harris Automatic Press Company had sold several machines into the empire and to rave reviews. Most likely companies like Komori had taken notice.

During the early 1920s, few westerners knew anything about the Japanese. Besides the arts-and-crafts business, Japan exported very little and travel was rare. In 1925, Komori’s first produced machine was a Planographic hand press (stone printing). This was a copy of America’s Fuchs & Lang lithographic press and of a very simple design. By 1928, Komori built a 32-inch hand-fed offset press – similar to the press in our museum. Early designs stemmed from duplication of English and American machines.

The Komori firm was run by the Komori family who today continue to control a large portion of its equity. The next three decades were rather uneventful and with the country’s military action in Manchuria, soon followed by entry into World War II, Japan was systematically locked out of technological developments that were taking place in America, Britain and Europe. Komori could only sit and watch while they busied themselves servicing the antiquated Japanese printing industry, as well as making attachments to allow automatic feeding of hand-fed machines.

In a 1997, a World Bank report explained, that after World War II, Japan lagged far behind the west technologically and didn’t compete internationally, but imported technology, which allowed them to enter a high-speed growth period referred to as the Gerschenkron model. This means it was a latecomer enjoying the accumulation of innovations developed in advanced countries. The Japanese word Manabu (to learn) and Manebu (to imitate) are key elements in all well respected Japanese manufacturer’s early beginnings. Komori was no exception and, considering its factory was destroyed by fire during the war, the company had few options but to rebuild, accumulate knowledge and try again. By December 28, 1946, Komori Machinery Works was finally incorporated into a joint-stock or public company.

By 1952, big things started to happen. Komori had finally built an automatic feed offset press. This press was fitted with the American Dexter feeder and delivered to Kyodo Printing Company. By 1956, one of its very first presses, a model KW-2 with a sheet size of 26 x 39 inches was exported to Canada. It went to Montreal. Years later that press made its way to the Quebec city of Sherbrooke and by the late 1970s sold again to a printer in Oakville, Ontario. It was scrapped in the early 1980s. In 1957, Komori Currency was started and a range of Intaglio Simultan-like presses were established. Komori presses have printed Japan’s banknotes ever since much to the chagrin of KBA-Giori.

The company continued to develop products, releasing a four-colour UM-4C in 1957, a five-colour in 1961 and a six-colour in 1963. That same year saw the introduction of the Kony and the Unikom models. Later the monster Kosmo, a unitized press built in the 45- and 50-inch formats, was launched. Komori marketed the Kony Super 9, then Super 10, in North America and Europe, but not the Kosmo.

Opening up Japan

The 1950s opened up Japan as much as the constrained government would allow. This proved beneficial to all manufacturers as many set sail for the engineering capitals of the world. Komori did the same, for the company was already well known in Japan. The period between 1950 and 1970 was an enigmatic time for most westerners when they viewed Japanese industry. In the graphic arts a scattering of firms made mostly facsimiles of almost everything. Even in the early 1970s, the famed English Wharfdale letterpress was still being manufactured in Japan. Hitachi Seiko also made a copy of the Heidelberg OHC cylinder press. As Japanese industrialization geared up, there was a lot going on besides cars and transistor radios.

Aside from a few exports there remained no western market for Japanese printing equipment. In fact, Germany never seemed too concerned about licencing technology to fledgling engineering firms. Sumitomo – a very large corporation – was building Miller-Johannisberg presses. Yoshino, perfect binding and trimming machines from Sheridan and Martini. Even KBA had its little KRO Rapida made for a while by Ryobi. But Japan did have its close neighbours and equipment flowed all over the area from China and Korea to Indonesia and the Philippines. Komori slowly carved out a market even though by the early 70s Mitsubishi, Ryobi, Shinohara, Fuji, Sakurai and Akiyama were playing in the same sandbox. Especially in the domestic market, Mitsubishi MHI proved to be a constant irritant and major competitor. Heidelberg continues to be a major presence in Japan to this day.

But few were building web presses. In 1970, Komori entered this market with the first of its blanket-to-blanket System series presses – System 25. Besides TKS, Hitachi and Toshiba, few dared competing in this segment. Goss for many years had some of its newspaper presses built here and the locals seemed to always prefer machines from the west. The 546-mm cut-off remains a favoured size in Japan and most of Asia and Komori catered to this cut-off, continuing to build this size today.

Also in 1970 someone must have seen the MAN or ColorMetal back printer. Komori added this feature to its Kosmo presses as an option. The back printer, or as Komori called it, reverse printer (RP), became a mainstay and well received addition. The RP continued with the Lithrone and won orders in carton printing for heavy board perfecting without the difficulty of building a perfector.

1970 was indeed a big year. Not only did Komori’s web program arrive, but this was the year of the Sprint series. The Sprint was a 25-inch press that started off as a one- and two-colour and then in 1971 a four-colour. These presses caught fire and featured a German Mabeg Jr. feeder head and electronic in-feed controls made by Omron (now house built as Eyekom). The Sprint series was so popular that it remained in production for more than 35 years. Press operators found it easy to run and it had very creative ancillaries over the years like delivery controlled plate register and Komorimatic continuous flow dampening. The later would graduate to the full line of sheetfeds and web presses. In 1976, the company name was changed to Komori Printing Machinery Co. Ltd.

Komori’s real breakthrough year was 1981. In that year, after exhaustive study and research, Komori came out with a press like no other, the Lithrone. This would be the moment German builders woke up and started to pay attention. What was this little company running out of three rather small manufacturing sites – Toride, Yamagata and Sekiyado – doing? And how could they possibly? I’m almost sure the former Heidelberg rebuild centre in Waldorf, Germany, was just a bit smaller than Toride.

Over the next four decades, starting with the Lithrone, Komori would drive a range of innovations into the press-building world with offset innovations, factory builds, metals, and now inkjet system transports and partnerships.

Lithrone impact

To get a grasp of the monumental changes that were brought by the engineer design of Komori’s new Lithrone platform in 1981, you must look back to 1965 and a company known as Planeta, in the former East Germany. Planeta was also rather isolated, locked behind The Iron Curtain, but the press maker had some brilliant ideas. Few in the rest of West Germany and Europe paid much attention when Planeta launched its Variant press platform, but Komori certainly did. The Japanese press maker quickly saw the benefits of the double-size impression and transfer cylinders on the Variant. Although the Kosmo was a unitized press, the Kony was a bit of a discombobulation of upper and lower unitized units. Komori saw the light and embraced the Planeta Variant’s forward-thinking unitized double-size cylinder design. Planeta is now a part of Koenig & Bauer.

Not everything Planeta was borrowed. Komori retained the upper swing arm first used on Miehles, then Rolands, and made its own version of the Mabeg feeder head and essentially improved or re-engineered every part of the Planeta design principles with a press that remains today as a watershed beacon of Komori engineering achievement. And it was fast. At 13,000 iph, the Lithrone eclipsed both Roland and Heidelberg by 3,000 iph in 1981. I could go on and on about various features but suffice to say the Lithrone made Komori what it is today. Twenty-six-, 28-, 44- and 50-inch Lithrones would soon enter production.

During the early 1980s, the packaging industry soon discovered the benefits of using aqueous coatings instead of varnishes. Komori became the first to build a factory tower coater. True – Planeta had done so earlier but these were simply printing units less the inker. Komori fashioned its own three-roll coating apparatus and followed Planeta’s lead by offering extended deliveries. Unless you ordered a hollow transfer Lithrone, however, running short-grain carton was not ideal. Both the solid and skeleton, or hollow cylinder, still only allowed substrates of up to .032 inches (0.8 mm). Roland and Heidelberg (1986) already eclipsed this and of course Planeta had the widest range up to 1.4mm or over .050 inches. This is why even today Koenig & Bauer still carries the reputation as the ultimate carton press. In 2017, when every manufacturer can essentially run the same caliper of board (including Komori), Planeta’s early penetration into that market continues to pay dividends for Koenig & Bauer.

Buoyed by its strong sales – especially into the U.S. and Europe, Komori pushed to acquire the Harris Graphics Corporation in 1988. In fact, Komori had made what it assumed to be a deal with the principle owner AM International, and even released a press statement confirming the acquisition. At that time, Harris web division was a leader in commercial and insert printing web systems. When the dust settled, however, Komori was trumped at the final hour by Heidelberger Druckmaschinen. No doubt anger sidelined Komori executives, but not for long as Komori swooped in to buy the small French specialist packaging narrow-web manufacturer Chambon. In retrospect, considering the depressing state of the web-offset business today, Komori may have been done a favour.

It’s in the metal

Komori grasped another sales tool. When Japanese exports took off in the early 1970s, the West handed out the moniker of “Japanese Junk,” from early cars that would rust away to machinery that would break from poor foundry methods. There were a lot of consumer products leaving Japan that had only one saving grace – price. This story is an old one and we have seen it reappear again with China’s entry onto the world stage. In short, made-in-Japan in 1970 meant inferior goods at very cheap prices. It’s incredible to consider how this has changed in less than 50 years.

I don’t know about you, but I can go for days without thinking about cast iron. But to machine builders, it’s a very important topic. Komori was well aware of the uphill battle it faced trying to export a machine that was about 80 percent cast iron. In fact just about every heavy machinery exporter did too.

Nebiolo S.p.A. of Italy faced the same backlash. With a tarnished reputation, Nebiolo turned to Meehanite to prove to the world their cast was as good as any. So Komori did a smart thing. Komori’s major castings come from a company called Kasakura Metech Co. and Kasakura became a certified Meehanite foundry in 1981, although its roots go back to 1919. Meehanite is a process to increase the quality of grey castings. It was developed back in the 1920s by the Ross Meehan Foundry in Chattanooga, Tennessee. Meehanite Corporation was formed to, among other things, license third parties to use the technology which essentially increased the Perlite and removed Ferrite from the cast, strengthening it.

Heidelberg, which owns its own foundry, already had a century of skill making superior castings, but Komori’s supplier was unknown outside Japan. Now Komori would emblazon their castings with the famous “M” logo in bas relief to show the world it could supply castings as strong as anyone. Ironically, Mitsubishi took a slightly different path when it did the unthinkable by having a non-Japanese company (Beiren of China), make much of theirs. Kasakura now has a foundry in China, too.

No one today should question the superior engineering of Komori presses. After all the upheaval in the offset business, Komori has remained the undisputed leader in Japan and one of the world’s top three press manufacturers in the world. Quite a feat for a company that always holds its cards close to the vest. Like Heidelberg, KBA and Manroland, Komori too finds the lithographic business dwindling from the highs of the 1990s as digital devices take more and more of offset’s position away.

Made in Japan and Israel

Landa Digital’s S10 press is already made up of Komori transport, coating and perfecting components. Komori signed an agreement with Landa to both provide traditional press components and also exclusively market its own version of the Landa S-10 as the Komori Impremia NS-40. Since there is no way yet to determine the success or failure of this platform, the industry sits and ponders if these very expensive Landa presses will be stars or dogs. Knowing Komori, I’d put my money on the former. However at eye-watering prices even as a success others will make that determination.

Konica Minolta also partnered with Komori on the smaller Impremia IS29. Komori even started selling its own guillotines in 2014. I didn’t really think the world needed another guillotine but… All the while Komori keeps selling new generation GL(X) 29- and 40-inch presses and perfectors to a satisfied user group of commercial printers. The crafty HUV-doped UV, which uses much less power and produces less heat, was a Komori-Iwasaki-EYE invention that for a brief few years had the market all to themselves. Now pretty much everyone has a low-energy UV alternative to offer.

Rarely first with new designs, Komori researches the market well. If a competitor’s leap is deemed important enough, you will see it worked into a Komori press. Just look at the up and over delivery from Manroland, vacuum feeder from Roland and Heidelberg, or even the Wallscreen and Inpress concepts from Heidelberg. They all made it into the Komori GL40 a few years later. There is also a flat line across all major press makers today as everyone makes an outstanding press.

Few know the inner workings behind the Japanese mystic, even fewer care. Mitsubishi MHI’s recent exiting of its sheetfed business, handing the keys to Ryobi, has not done much to eliminate a competitor. If, as many suspect, the Mitsubishi Web program may be shuttered or sold off entirely, the landscape may only alter inches not feet.

There is a source of puzzlement when benchmarking Made in Japan with the rest of the world. Certainly exporters are heavily supported by government incentives (as well as periodic tax benefits for the domestic market), and almost all Japanese branch units run lean with very low head counts. With such world-acclaimed products, some find it ironic that basic functions such as spare parts and communication vary greatly from region to region. The Germans remain leaders with greater transparency in customer relations. In short, to outsiders it seems the only thing holding back Japanese companies is in fact themselves.

When Toyota was named the world’s largest car company in 2016, it might have been a statement that some in the automotive industry questioned. Not the fact that Toyota was the largest and so successful, but why it took them so long.

Virtually every manufacturing segment has a Japanese company ranked at or near the top. Komori is no exception. The new super factory/assembly hall opened in 2003 in Tsukuba, Japan, was years in the planning and built with the next technology leap in mind. KANDO, the new catchword meaning, as Komori interprets: “Beyond Expectations… is an expression of who Komori wants to be and why it’s important to you.”

Every press manufacturer has a few product embarrassments in their closets. Some more than others. No one is exempt. In Komori’s case they have been rather fortunate in successfully dodging major blunders over its 94 years. Not only do they have a dedicated following but their management team has taken great pains to run a conservative, profitable world-class company.

The year 2018 marks Komori’s 95th year in business and a very good reason to celebrate a special company that from 1923 to now has been in the offset business almost exclusively. You may not see Komori race out in front of the pack in a marathon, but you will sure see them at the finish line.

Print this page