Expanded gamut printing continues to grow in popularity, but does this process to exclude spot colours have long-term staying power for commercial printers to invest. At Ryerson University’s 2017 GCM Colloquium, called SPECTRUM+ by its student organizers, three industry leaders weigh in: Colour scientist John Seymour; Kyle McVey, Director of Client Services, Jones Packaging; and Nawar Mahfooth, Chief Science Officer, ColorXTC.

Expanded gamut is an idea tracing back to 1960 when the printing process was first applied to the production of Hallmark Cards, many of which used pastel pinks and blues found on the extreme edges of the CMYK gamut. The card company developed a scheme where it added a light blue and a light pink, as well as some fluorescents to some of the inks, and created its trademarked BigBox Color system. Today, 57 years later, the money-saving potential of expanded gamut printing is on the minds of thousands of printers around the world.

Applied mathematician and colour scientist John Seymour, speaking at Ryerson University’s Graphic Communications Management 2017 Colloquium, called SPECTRUM+ by its student organizers, describes the Hallmark Card scenario as the first-known example of expanded gamut work. Seymour began his career in advanced product development in 1992 for QuadTech, working with instruments for improving the measurement and control of colour in print manufacturing.

He is one of three speakers to discuss the opportunities of expanded gamut at the February SPECTRUM+ event, in addition to Kyle McVey, Director of Client Services, Jones Packaging, and Nawar Mahfooth, Chief Science Officer, ColorXTC. McVey described three days of recently completed expanded gamut trails undertaken by Jones, one of North America’s most-prominent packaging printers, and Mahfooth focused on ColorXTC’s Dynamic Press Profiling (DPP) technology, a remote offset press profiling service to provide press characterization data without the expense of dedicated runs. Instead of running more than 1,600 patches in testing, DPP applies proprietary algorithms to a smaller profiling target (150 patches) gathered in an regular production run.

Seymour’s presentation, entitled When an Idea’s Time Has Come, focused on the maturation of expanded gamut and the opportunities it provides for printing companies. He contends the new awakening of expanded gamut (EG) revolves almost exclusively around saving money – not building a better mousetrap, but rather a cheaper mousetrap.

Building mousetraps

It took eight years after Hallmark Cards’ 1960 BigBox Color system, Seymour explains, for an expanded gamut patent to be filed in 1968 by Dainippon Screen, whose patent abstract explains, “[printing plates] are produced for reproducing colour images with inks other than the standard inks.” The year 1985 brought the next major EG patent filed by Harald Kueppers, whose work, Seymour explains, did not go far because it was manually intensive to go beyond four process colours, making separations.

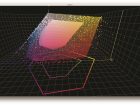

Kueppers’ work, however, is recognized as a foundation of EG development, as described by his patent abstract: “Whereby the elemental surfaces which form the chromatic component are printed with a maximum of two of six chromatic printing inks, yellow, magenta-red, violet-blue, cyan blue, green and black.” A range of base ink colours, of course, can be added to traditional CMYK to expand a gamut for a reoccurring printing process, but the prevailing model is most likely to be determined by the sector’s colour power of the day. “In expanded gamut printing, we move from four-colour printing to seven-colour printing and our base set of process colourants is now seven colour, which can be different for different systems,” writes Dr. Abhay Sharma, one of the world’s foremost colour experts and professor with Ryerson University. “For example, the new Pantone+ Extended Gamut swatch book is printed using CMYK plus Orange, Green and Violet (OGV)… The swatch book is available as a traditional swatch book as well as in software – Pantone Color Manager – and shows how spot colours would be reproduced in seven colours, CMYK + OGV.”

Seymour explains Pantone filed a significant EG patent in November 1994, part of a one-year period the colour scientist refers to as the heyday of expanded gamut printing patents. Invented by Richard Herbert, son of Pantone’s founder, this work became known as Hexachrome based on the use of six extra-pure inks (CMYK + OG), some containing fluorescent components. Hexachrome books were around for 20 years before fading away.

From March 1994 to March 1995, ink and imaging scientists with Pantone, Du Pont, Kodak, Barco Graphics, Opaltone and Linotype-Hell developed a range of EG innovations. Du Pont’s work was led by Don Hutcheson, well known for the G7 calibration process and GRACoL, who is now a driver behind Idealliance’s newly minted XCMYK methodology for EG printing. XCMYK remains a four-colour CMYK process but uses inks that are blended to be much purer than regular inks. Promoting the idea that more ink means more colour, leveraging FM screening, the XCMYK dataset and profiles can reproduce a larger gamut than that of GRACoL. Idealliance emphasizes XCMYK is not a replacement for GRACoL but rather an alternative colour space.

“FM screening actually gives you a bigger profile, a bigger gamut, not because the solids are pushed up,” says Seymour. “Obviously, FM screening doesn’t make the solids any richer, but it bows your profile up so you pick up more of the pastels.”

Opaltone, also patented during the mid-90s EG heyday, is still being used today primarily in toner-based printing. None of these heyday patents attempted to encapsulate the entire concept of EG, but rather coincided with a significant printing evolution. “Patents are almost always for incremental processes, small improvements on what is already there,” says Seymour, who himself has 22 patents. “So we have five patents and they may overlap a little bit, but they are all distinctly different.”

Seymour explains the EG heyday patents arrived during the widespread adoption of digital prepress technologies, bolstered by a matured desktop publishing sector. “Innovation happens when you have a need that also needs technology,” he says. “You finally have the digital technologies to allow you do to the [EG] separations – that is when innovation becomes possible.”

In reference to the need itself, Seymour points to the desire for the printing industry at large to create better quality pictures within an expanded gamut process. “You do get more colour. You can get more gamut out of it when you have those additional inks,” he says. This colour-punch need reverberates with designers and consumers. On the pressroom floor, however, the potential benefits of EG are measured in time and resources – dollars – saved.

Seymour relates the awakening of EG directly to the printing industry’s need to increase margins in a market of overcapacity and technological innovation. “The market for a better mousetrap is pretty small because if [the current trap] already catches most of your mice, are you going to spend a lot of money getting a new one, a better one – I don’t think so,” he says. “How about getting a cheaper mousetrap – yeah, there is a market for that. This is a large market.”

There are enormous cost savings available to a printer who can regularly run an EG gamut – without the need to wash-up after each run – on press to reproduce or closely simulate a range of brand colours, which have traditionally been printed with special spot colours poured into the fifth-plus press unit, which needs to be cleaned up when the run is done. The ability to simulate brand colours without press wash-up is the main draw of EG printing. It relates to decreasing the need to buy spot colour inks and hold inventory. Running an EG process with a consistent larger gamut also holds the potential to gang-run more high-value work up on a sheet, instead of low-margin CMYK jobs – often holding less than four process colours.

“The driving force of expanded gamut is not so much the ability to make pretty pictures. It is about saving money, that is the whole reason why we are trying to get into it,” says Seymour. “That is why you are spending so much money for those three days on press, pulling out your hair, trying to figure out how to make this happen… trying to save money.”

Expanded gamut trials

McVey began working at Jones Packaging of London, Ontario, in 2003 as a graphic designer, after graduating from Fanshawe College, and showed an affinity for learning about the printing process, working in prepress design and structural packaging. In addition to printing, Jones’ two other divisions include contract packaging services (bulk handling of pharmaceuticals) and a health-care division working directly with hospitals and pharmacies across North America and into Spain and the United Kingdom. Taking on a managerial position, McVey then began working in Jones’ plate room and consulted with the pressroom on technical issues – a liaison between sales and production, running both litho and flexo presses.

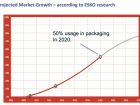

A year and a half ago, McVey began working with Jones’ pressroom supervisor on a three-day trial of expanded gamut printing. A prospective client, described as very large with product across North America, approached Jones and other existing print suppliers, with a desire to run EG for packaging. EG is primarily applied in commercial print today, but beginning to find its way into the packaging sector where brand owners relish the pop of colour available in an expanded gamut, for example, to make flowers vibrant or people look less washed out – often accomplished today with expensive ink modifications or second hits of the same colour.

Moving to EG printing, however, would mean forgoing the power of brand-specific inks, which is the CMYK-plus-spot environment in which McVey developed his career, witnessing firsthand the pressure it puts on the prepress world. The prospective EG client ask involved CMYK + OG, not the full Orange, Green, Violet Pantone EG spectrum.

Jones would trial the work on its six-colour Heidelberg Speedmaster press, with coater. The client wanted the print suppliers to produce 10 of its leading brand packages using six-colour process expanded gamut print. Each package was identified and measured using two brand colour patches, which were Pantone EG matches of their brand colours. “L*a*b* values, ink densities, and tonal value increases were supplied to us through a Kodak proof… and for each brand defined target patch there was a request that it did not exceed 2.5 delta E,” says McVey, “which I think is being pushed as a kind of industry standard. This is where printers are going to have a problem with expanded gamut.”

Jones’ EG testing applied conventional CMYK + OG water-based inks and coatings across all products, running on coated recycled board, as opposed to preferred SPS board, the latter of which accounts for more than 90 percent of Jones’ substrate usage. The artwork separation was done by a prepress house using Esko software to create a Euclidean dot. McVey explains the ink sequence on press was Green KCMY and Orange, based on the fact that Jones currently runs the Heidelberg’s centre four units as KCMY – acknowledging an ongoing debate in packaging, where a majority of shops run a more traditional CMYK sequence. “We chose to put green at the front of the press because it had the least impact on all of the brands that we were printing,” says McVey, “so the dot gain would be minimized on that specific colour and we put orange at the end.”

McVey explains Jones ran 12 press tests, purposely changing conditions, to adjust their plate curves and create a solid linear set for approximately 20 brands colours on the press form, aiming to get as many of those brand colours under 2.5 delta E as possible. L*a*b* values built from the perfect the dots and laydown of the Kodak proof presented an immediate challenge. “There may be some colours that were already at a 2 delta E just on the Kodak alone, so we basically had a 0.5 delta E to work with printing on a press, with all of the variables.”

Among common press issues like registration, ink density and ink trapping ink, the latter variable would prove to be most challenging in the EG tests. Jones produced the full range of 20 brand colours at under 2.5 delta E using EG, but not without some fixes. “At about 75 percent of a colour with certain blends, specifically cyan and magenta, we were seeing a lot of ink-trapping issues,” says McVey, noting how conventional water-based inks have a tendency to blend on a litho press. “Printing cyan and magenta [at] 100-100 laydown is not predictable and due to that, due to the ink trap of those two values, this was our hardest colour to try and match, to keep under 2.5.”

Jones’ production team was able to average 2.3 delta E in its cyan-magenta tests, but they had to actually reduce the magenta ink. “This is not what you want to do in expanded gamut. It is not consistent throughout the jobs… now you have a different ink and you might as well [put] a spot colour in there,” says McVey, noting this information was passed on to the client. Understanding the importance of setting expanded gamut expectations, Jones provided the client with a long list of recommendations, such as the challenges of working with perfect Kodak proofs, the importance of ink sequence and tight press controls, and ultimately the consulting of print expertise in addition to a prepress house.

“Expanded gamut printing is just one tool in the printing industry’s massive tool box,” says McVey. “Really take it upon yourself when you are in a discussion about expanded gamut to actually learn about what is necessary to make it successful for that application.”

Print this page